Adaptations for Engaging Children with Disabilities in STEM Storybooks

Posted on June 25, 2020 in Storybook Conversation

Adapted storybooks are an easy and inexpensive way to help children with sensory, visual, motor, and linguistic differences to access STEM learning through reading. While dialogic (DR) and shared interactive book reading (SIBR) strategies have been shown to support children with and without disabilities in engaging with books (Lonigan et al., 2008; Mendez et al., 2015; Fleury & Schwartz, 2017; Towson et al., 2017), many children may also benefit from tangible adaptations and modifications to the book itself.

Adapted storybooks are an easy and inexpensive way to help children with sensory, visual, motor, and linguistic differences to access STEM learning through reading. While dialogic (DR) and shared interactive book reading (SIBR) strategies have been shown to support children with and without disabilities in engaging with books (Lonigan et al., 2008; Mendez et al., 2015; Fleury & Schwartz, 2017; Towson et al., 2017), many children may also benefit from tangible adaptations and modifications to the book itself.

Adapted books can be categorized as a form of augmentative and alternative communication (AAC). Some readers may be familiar with adapted books from seeing their efficacy with children with visual impairment (Brennan, et.al.,2009; Lewis & Tolla,2003), significant intellectual impairment (Erickson et al., 2010) significant motor or communication impairment (Light et al. , 1994; Light & Kent-Walsh, 2003), or autism spectrum disorders (ASD, Carnahan et al., 2009).

However, adapted storybooks can promote access and engagement for all children in DR (Justice, 2006), and DR may provide an important scaffold for children’s understanding of more abstract content (Gonzalez et al., 2011). Abstract content in STEM may include more complex “academic” words featured in many informational and expository science books (“evaporation”, “reptile”), and that don’t appear in every-day conversation. Families that read expository books together are more likely to have longer, more complex conversations about the books afterward, and those conversations feature more diverse vocabulary (Price et al., 2009). Moreover, diverse academic vocabulary is essential to later reading success (Beck et al., 2008), yet many children with disabilities may struggle to access and comprehend it.

Storybook props and adaptations are therefore an important means of supporting STEM access for young children with disabilities. Many “high-tech” resources are now easily accessible for augmenting STEM storybooks, through tablets that support picture software such as Picture exchange communications (PECS) systems (Frost & Bondy, 1998), Boardmaker (Mayer-Johnson, 2002) and electronic storybook apps such as Tar Heel Reader (tarheelreader.org). However, “low-tech” resources are often more easily reproducible at home, and may be more durable and feasible for families to implement than expensive software.

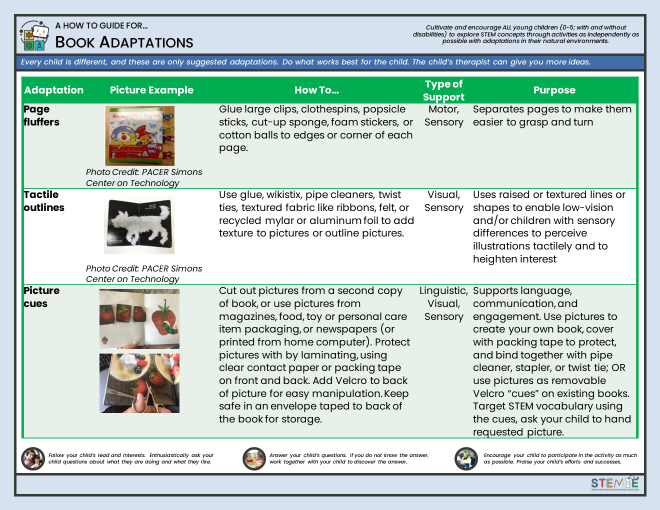

The chart below outlines 7 easy at-home storybook adaptations, categorized by the type of support they may provide (motor, sensory, communicative/linguistic, visual, or auditory).

References

Beck, I. L. McKeown, M. G., & Kucan, L. (2008). Bringing words to life: Robust vocabulary instruction (2nd Ed). New York: The Guilford Press.

Brennan, S. A., Luze, G. J., & Peterson, C. (2009). Parents’ perceptions of professional support for the emergent literacy of young children with visual impairments. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 103, 694–704

Carnahan, C., Basham, J., & Musti-Rao, S. (2009). A Low-technology strategy for increasing engagement of students with autism and significant learning needs. Exceptionality, 17(2), 76–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/09362830902805798

Erickson, K. A., Hatch, P., & Clendon, S. (2010). Literacy, Assistive Technology, and Students with Significant Disabilities (Vol. 42).

Fleury, V. P., & Schwartz, I. S. (2017). A modified dialogic reading intervention for preschool children with Autism Spectrum Disorder. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 37, 16–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271121416637597

Frost, L. & Bondy, A. (2002) The picture exchange communication system training manual. Newark, DE: Pyramid Educational Products.

Gonzalez, J. E., Pollard-Durodola, S., Simmons, D. C., Taylor, A. B., Davis, M. J., Kim, M., & Simmons, L. (2011). Developing low-income preschoolers’ social studies and science vocabulary knowledge through content-focused shared book reading. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, 4, 25–52. https://doi.org/10.1080/19345747.2010.487927

Justice, L. M. (2006). Clinical approaches to emergent literacy intervention. Plural Publishing.

Lewis, S., & Tolla, J. (2003). Creating and using tactile experience books for young children with visual impairments. TEACHING Exceptional Children, 35, 22–29. https://doi.org/10.1177/004005990303500303

Light, J., Binger, C., & Smith, A. K. (1994). Story reading interactions between preschoolers who use AAC and their mothers. Augmentative and Alternative Communication, 10, 255–268. https://doi.org/10.1080/07434619412331276960

Light, J. C., & Kent-Walsh, J. (2003). Fostering Emergent Literacy for Children Who Require AAC. The ASHA Leader, 8, 4–29. https://doi.org/10.1044/leader.ftr1.08102003.4

Lonigan, C. J., Shanahan, T., Cunningham, A., & The National Early Literacy Panel (2008). Impact of shared-reading interventions on young children’s early literacy skills. In National Early Literacy Panel (Ed.), Developing early literacy: Report of the National Early Literacy Panel: A scientific synthesis of early literacy development and implications for intervention (pp. 153– 171). Jessup, MD: National Institute for Literacy. Retrieved from https://lincs.ed.gov/publications/pdf/NELPReport09.pdf

Mayer-Johnson, I. (2002). Boardmaker. Windows version 5.1.1. Solana Beach, Calif. : Mayer-Johnson, Inc. https://search.library.wisc.edu/catalog/9910538690202121

Mendez, L. I., Crais, E. R., Castro, D. C., & Kainz, K. (2015). A culturally and linguistically responsive vocabulary approach for young Latino dual language learners. Journal of Speech, Language, and Hearing Research, 58, 93-106.

PACER Simons Center on Technology. (2017). Young Children, AT, and Accessible Materials – YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pN280lcuR24&feature=youtu.be

Price, L. H., Kleeck, A., & Huberty, C. J. (2009). Talk during book sharing between parents and preschool children: A comparison between storybook and expository book conditions. Reading Research Quarterly, 44, 171–194. https://doi.org/10.1598/rrq.44.2.4

Towson, J. A., Fettig, A., Fleury, V. P., & Abarca, D. L. (2017). Dialogic reading in early childhood settings: A summary of the evidence base. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 37, 132–146. https://doi.org/10.1177/0271121417724875